Opaque types is a great technique in Elm. It prevents misuse of a custom type by restricting the possible operations you can apply to it, and it reduces coupling allowing you to change implementation details without impacting the rest of the codebase. We've talked about quite a bit on a dedicated Elm Radio episode.

Every so often, I see people ask what to do when you need the hidden constructors in the tests. If you keep the constructors hidden, then you can't write the tests you want to have. If you expose the constructors, you lose the benefits listed above.

Problematic example

In the following example, we have an opaque custom Role type with two variants. The Admin variant is being protected so that the only way to create one is by having the server return that the user has that role.

module Role exposing (Role, canDeleteDatabase, requestRole, user)

import Http

import Json.Decode as Decode exposing (Decoder)

type Role

= User

| Admin

user : Role

user =

User

requestRole : (Role -> msg) -> String -> Cmd msg

requestRole onResponse id =

Http.get

{ url = "https://server.com/user/" ++ id

, expect = Http.expectJson onResponse roleDecoder

}

roleDecoder : Decoder Role

roleDecoder =

Decode.field "role" Decode.string

|> Decode.andThen

(\role ->

case role of

"admin" -> Decode.succeed Admin

"user" -> Decode.succeed User

_ -> Decode.fail "Not a valid role"

)

canDeleteDatabase : Role -> Bool

canDeleteDatabase role =

case role of

User -> False

Admin -> TrueWe have a good foundation with this approach, in the sense that it won't be possible for someone to have an Admin role without the server's consent (the approach could be improved, but let's say it is sufficient for the sake of this example).

The problem is that we won't be able to write tests that require an Admin role, because it is not possible to construct such a value in our tests. We would would need to make an HTTP request, which elm-test doesn't support.

module RoleTest exposing (roleTest)

-- imports...

roleTest =

Test.describe "Role"

[ Test.test "admins should be able to delete database " <|

-- Error: Role.Admin is not exposed!

\() -> Expect.true (Role.canDeleteDatabase Role.Admin)

, Test.test "users should not be able to delete database " <|

\() -> Expect.false (Role.canDeleteDatabase Role.user)

]The common solution is therefore to either expose the Role (exposing Role(..)) or to expose a function to construct

Role, like we did with user.

module Role exposing (Role, canDeleteDatabase, admin, requestRole, user)

type Role

= User

| Admin

user =

User

admin =

AdminNow the problem is that we lost the foundation we had, where a user could be Admin only if the server said they were.

Now such a case would only be caught during code review where the reviewer would have to make sure the role is never abused.

Proposed solution

The solution I would go for in the previous example would be to expose values (or functions) to construct Role, but tag them as "test-only" values, meaning that we should only use them in test code. And using an elm-review rule, we'd get the guarantee that this is the case.

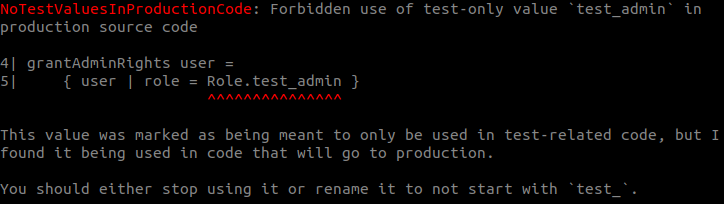

I have just published a new package named jfmengels/elm-review-test-values, which contains the NoTestValuesInProductionCode rule. The rule enforces that test-only values found in your source code are only used in test code, never in production-facing code.

Tagging is done through a naming convention of your choice. The available options are to prefix or suffix the names of the functions.

-- NoTestValuesInProductionCodeTest.startsWith "test_"

grantAdminRights user =

{ user | role = Role.test_admin }

-- NoTestValuesInProductionCodeTest.endsWith "_TESTS_ONLY"

grantAdminRights user =

{ user | role = Role.admin_TESTS_ONLY }

Once you add this rule to your configuration, you can safely expose a tagged constructor value and write the tests you wished to write originally.

module Role exposing (Role, canDeleteDatabase, requestRole, test_admin, user)

type Role

= User

| Admin

user =

User

test_admin =

Adminmodule RoleTest exposing (roleTest)

-- imports...

roleTest =

Test.describe "Role"

[ Test.test "admins should be able to delete database " <|

\() -> Expect.true (Role.canDeleteDatabase Role.test_admin)

, Test.test "users should not be able to delete database " <|

\() -> Expect.false (Role.canDeleteDatabase Role.user)

]The custom type is still opaque and even though the protected values are exposed, the rest of the codebase can't misuse it, effectively keeping the benefits of an opaque type.

Note for those wondering: Values tagged as test-only can be used in the declaration of other test values, as they themselves will not be allowed in production-facing code.

module User exposing (test_admin_user)

-- imports...

test_admin_user =

{ id = "001"

, role = Role.test_admin

}Alternative solutions

I would be remiss if I didn't point out that testing is most effective when testing at the right level. You want to test the public interface, not the details. Sometimes that is not possible, or it is impractical because the public interface makes it hard to test the edge-cases.

In that case I think that the solution I am proposing is a good balance between exposing too little and exposing too much details, though the more you use test-only values, the more you couple your tests to the implementation of the tested interface.

Let's look at other potential solutions for comparison.

Tagging through the documentation

Another solution would be to tag a value in its documentation.

{- Admin

TESTS-ONLY

-}

admin =

AdminBut that would be just as brittle. And it will be less obvious to code reviewers and future maintainers of the codebase that a value should not be used in production code, especially when the documentation of the function is not shown in the Git diff.

Putting tests inside the module

This is probably the most common suggestion I found: Put tests inside the module you wish to test. I am not a fan of the solution:

- You are more likely to test implementation details rather than the public interface

- Your code now depends on

elm-explorations/test. Unless you do something weird with the tests, they and the dependency should be pruned from the production bundle though. - The tooling now needs to know that tests can be in the source code.

You need to run

elm-test src/ tests/instead of justelm-test(and potentially let your colleagues know that), configure your IDE to do the same (if that's even possible. It's not in IntelliJ as far as I know),elm-reviewrules need to be aware of it, etc.

Critique

Is tagging values as test-only a perfect solution? No. Tagging values by name is a brittle solution as it's easy to misname a function (testadmin instead of test_admin for instance) and lose the guarantees this rule has given you.

I think this brittleness will rarely be a problem in practice, because even if the rule doesn't enforce anything, having something called testXyz will likely be a good enough indication to prevent misuse in practice. Otherwise I don't understand why so many frameworks encourage "convention over configuration" in other ecosystems.

For this rule to work well, the naming convention for test-only values needs to be communicated to the rest of your team or project. Otherwise, your teammates will expose values that should in practice be test-only without the proper name and therefore without elm-review's backing. Or worse, they will not write any tests at all.

Unused code

The biggest downside with this solution that I could find is that for values imported in tests, it becomes much harder to tell whether they are imported to be tested or to enable testing.

At some point, I would like to have NoUnused.Exports report exposed values that are only used in tests. It's good to have tests for your API, but if that API is only found in tests and not in production, you can probably remove all of that.

Test-only values would by definition only be used in test code, so they would be reported by future NoUnused.Exports, even though they are essential to the tests of a public API that is probably used. So we would have to configure NoUnused.Exports to know about test-only values. This is the same kind of problem as for elm-test, but the solution seems less intrusive. I still have to ponder this one, but as the author of both rules, I think I would be okay with that.

New and/or unconventional solutions have a tendency to have an impact on tooling, which I think people don't realize enough. Whether the downsides are worth it is a matter of balance of the pros and cons and judgment.

Try it out

You can try this rule out by running the following command:

elm-review --template jfmengels/elm-review-test-values/example --rules NoTestValuesInProductionCodeTestIf you haven't installed elm-review (npm install -g elm-review) but have Node.js, you can prefix the command above by npx (it will be slower to start though). Add --watch if you really want to play around.

The example is configured with NoTestValuesInProductionCodeTest.startsWith "test_", meaning it will consider functions that start with test_ as test-only values.

If you like this approach, you can add elm-review (1) and this rule (2) to your project by doing the following steps:

cd your-project

# (1) Init your project with a config I would recommend to start with.

elm-review init --template jfmengels/elm-review-unused/example

# Have fun with the errors it already reports

elm-review

elm-review --watch

# Get to know the tool

elm-review --help

# (2) Then install this dependency

cd review

elm install jfmengels/elm-review-test-values

cd ..(Still 2) Then add the following code to your review/src/ReviewConfig.elm file

import NoTestValuesInProductionCodeTest

config =

[ -- your other rules

, NoTestValuesInProductionCodeTest.rule

(NoTestValuesInProductionCodeTest.startsWith "test_")

]And you're good to go. If you need something slightly different for your use-case, you can instead copy it to your review/src/ folder and modify it to your needs.

If you're curious, you can look at the source code and the tests.